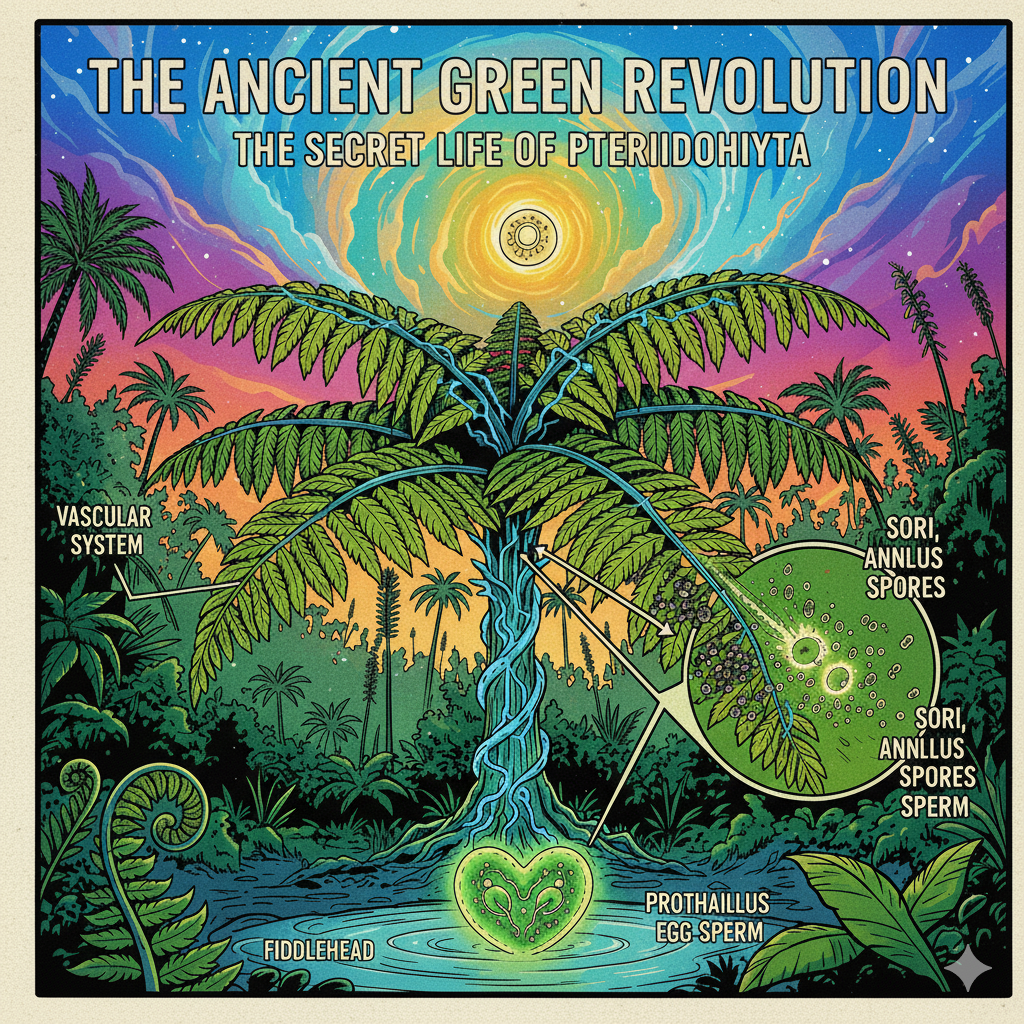

The Ancient Green Revolution: A Complete Guide to the Secret Life of Pteridophyta

Before flowers claimed the spotlight and before seeds became the ultimate botanical strategy, there was a group of pioneers that conquered the land with nothing but spores and a dream. Welcome to the world of Pteridophyta—the ferns and their allies. These aren’t just the decorative plants sitting in the corner of your local coffee shop; they are living fossils that witnessed the rise and fall of dinosaurs.

In this guide, we will peel back the layers of these “vascular pioneers” . We’ll dive into their strange reproductive habits, their complex plumbing systems, and why they are much more than just a pretty green leaf.

The Blueprint of a Survivor: General Characteristics

If you want to understand a fern, you have to look at its “plumbing.” Unlike the mosses that preceded them, Pteridophytes were among the first to develop a vascular system. This means they have internal “pipes”—xylem and phloem—to transport water and nutrients, allowing them to grow much taller than their mossy cousins.

Most ferns follow a distinct structural rhythm. Their plant body, known as the sporophyte, is the dominant phase you see in the forest.

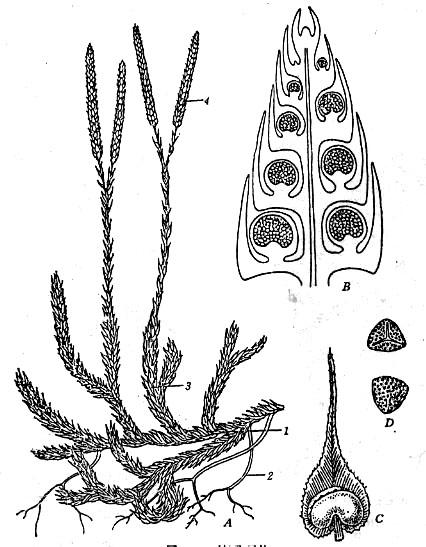

- Roots: They possess adventitious roots that anchor them firmly into the soil or bark.

- Stems: Often hidden underground, many ferns have rhizomes —horizontal stems that creep along the surface.

- Leaves: Pteridophytes have two main leaf types. Microphylls are simple, small leaves with a single vein, found in primitive types like clubmosses. Megaphylls, the classic fern fronds, are complex, branched, and evolved for maximum photosynthesis.

The Great Divide: Classification and Representatives

The world of Pteridophyta is vast, with over 12,000 species globally. Scientists generally divide them into five sub-phyla, each with its own “personality.”

The Minimalists: Psilophytina

These are the most primitive. Take Psilotum nudum for example. It lacks true roots and leaves, appearing as a series of green, branched sticks. It’s as if evolution decided to see how little a plant could have while still surviving.

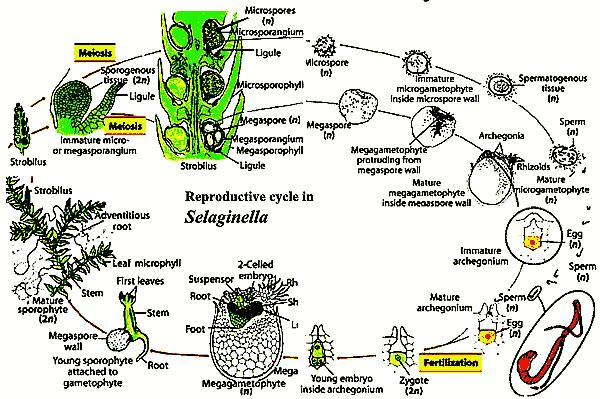

The Forest Carpets: Lycophytina

Ever seen a plant that looks like a miniature pine tree crawling on the ground? That’s likely Lycopodium . A key member here is Selaginella , often called the “Resurrection Plant” because it can survive extreme dehydration, curling into a ball and turning green again when it rains.

The Living Scouring Brushes: Sphenophytina

Commonly known as horsetails or Equisetum , these plants are unmistakable. Their stems are ribbed, hollow, and jointed. Historically, people used them to scrub pots because their tissues are packed with silica—nature’s sandpaper.

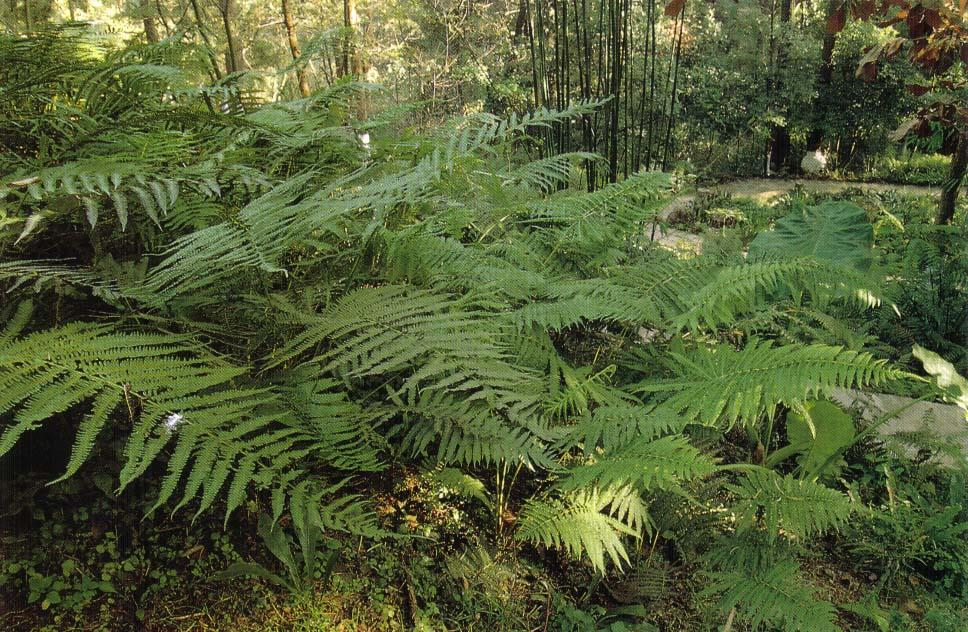

The Main Event: Filicophytina

This is what most people think of as “true ferns.” This group includes everything from the common Pteridium to the majestic tree ferns like Alsophila . They are categorized by how their sporangia develop—whether they have thick walls (Eusporangiatae) or thin walls with a specialized “ring” called an annulus .

The Secret Life Cycle: A Tale of Two Generations

If humans lived like ferns, we would spend half our lives as microscopic heart-shaped creatures living in the mud. This is the Alternation of Generations .

- The Giant Phase (Sporophyte): The fern you see in the woods produces millions of tiny spores. These are often tucked away in clusters called sori on the underside of the leaves.

- The Tiny Phase (Gametophyte): If a spore lands on moist ground, it grows into a prothallus —a tiny, green, heart-shaped structure.

- The Love Story: On this tiny heart, the plant produces sperm and eggs. Because fern sperm have “tails” (flagella), they literally have to swim through a film of water to reach the egg. This is why ferns love damp places—they need the water to “hook up.”

- The New Beginning: Once fertilized, a zygote forms, and a new sporophyte grows directly out of the tiny heart-shaped parent.

Why Should We Care? The Economic and Ecological Impact

Ferns aren’t just ancient relics; they are heavy lifters in our ecosystem and economy.

- Ancient Fuel: The coal we burn today? Much of it comes from the compressed remains of giant fern forests from the Carboniferous period.

- The Foodie’s Choice: In many cultures, “fiddleheads” (the coiled young fronds of ferns like Pteridium) are a seasonal delicacy.

- Nature’s Bio-Fertilizer: Azolla , a tiny water fern, has a symbiotic relationship with blue-green algae that fixes nitrogen. It’s used in rice paddies as a natural fertilizer.

- The Soil’s Voice: Some ferns act as indicator plants . For example, Dicranopteris tells you the soil is acidic, while Adiantum suggests alkaline conditions.

Conclusion: The Quiet Conquerors

The Pteridophytes are a masterclass in adaptation. They moved out of the water, built a vascular highway, and mastered a life cycle that bridges two worlds. Whether they are acting as the “sandpaper” of the forest floor or the “green manure” of a rice paddy, ferns remind us that you don’t need flowers to be successful—you just need a good set of pipes and the patience of an ancient survivor.