The Emerald Footprint: A Deep Dive into the Bryophyte Revolution

From the Primordial Splash to the Silent Carpet—How the “Amphibians of the Plant World” Engineered the First Terrestrial Ecosystems.

Introduction: The Silence of the Silurian

Imagine a world without birdsong, without the rustle of leaves, and without the scent of soil. Four hundred and fifty million years ago, during the late Ordovician and early Silurian periods, the Earth’s continents were a haunting, jagged expanse of barren rock and volcanic ash. While the oceans were already teeming with the sophisticated eukaryotic algae we discussed in Episode 5, the land was a “death zone” of intense UV radiation and extreme temperature fluctuations.

Then, the Bryophytes performed the ultimate leap of faith.

They did not arrive with the swagger of towering oaks or the vibrant colors of wildflowers. Instead, they arrived as a subtle, resilient emerald film. They were the first Embryophytes—plants that chose to protect their offspring in a multicellular “womb” (the embryo), a strategy that would eventually allow life to conquer the highest mountains and the deepest valleys. This wasn’t just a biological shift; it was a planetary terraforming project. In this 2,000-word deep dive, we will peel back the layers of these humble pioneers to see the complex machinery that allowed them to colonize a lifeless world.

I. The Architecture of a Non-Vascular World

To understand a moss, you must first understand what it lacks. They are the “un-plumbed” masters of the botanical world. While later plants developed the Xylem (to transport water upward via negative pressure) and Phloem (to distribute sugars via osmotic flow), the Bryophytes operate on a much more intimate, localized scale.

1. The Rhizoid: The Anchor of the Avant-Garde

We often mistake Rhizoids for true roots, but their function is fundamentally different. In a vascular plant, roots are a sophisticated mining operation, seeking water and minerals deep underground. In bryophytes, rhizoids are more like biological “anchors.” They are often just single-cell filaments or simple chains of cells that lack any conductive tissue. They don’t pump water; they simply hold the plant in place, allowing it to cling to vertical cliff faces or shifting sands. This lack of a central root system means bryophytes are limited by height—gravity is an enemy they cannot defeat without the structural support of lignin.

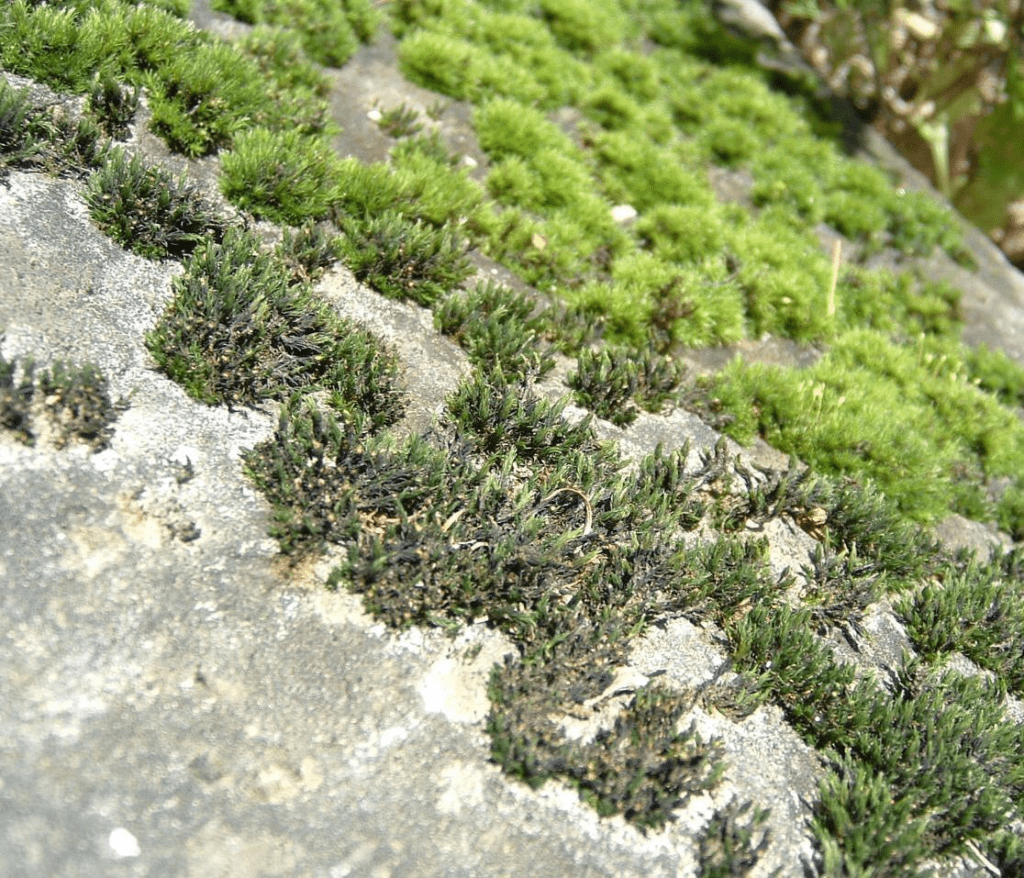

2. Poikilohydry: The Art of Living with Thirst

Because they lack a waxy cuticle (the waterproof “skin” of higher plants), bryophytes are poikilohydric. Their internal water content fluctuates in equilibrium with the humidity of the surrounding air. To a human, this sounds like a death sentence. To a moss, it is a superpower. When the environment dries out, the moss doesn’t die; it enters a state of desiccation tolerance. Its metabolism grinds to a halt, its cells shrink, and it waits. The moment a single drop of rain hits it, the moss rehydrates in seconds, resuming photosynthesis as if nothing had happened. This is why moss can survive on a sun-baked rock where even a cactus might struggle.

II. The Three Pillars of Bryophyta

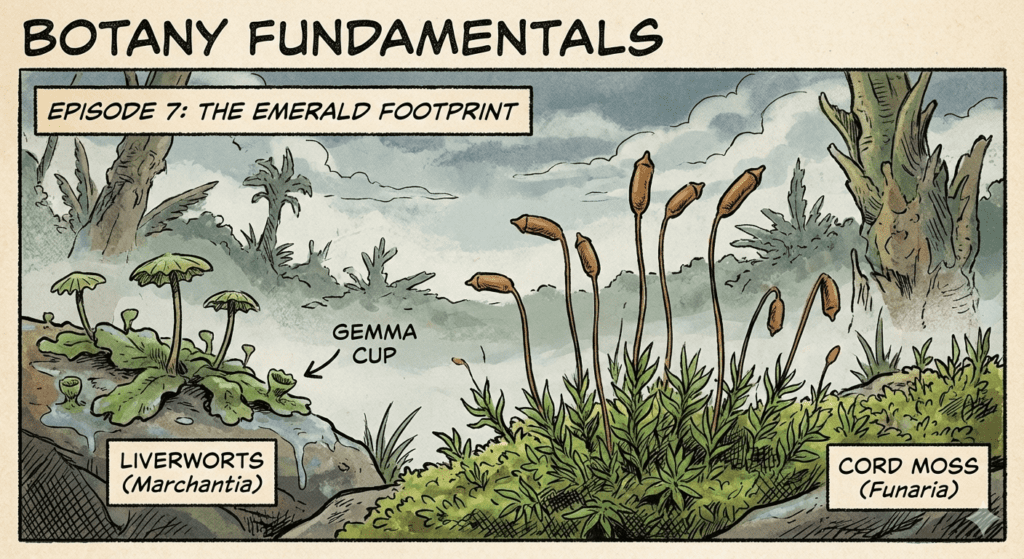

The PDF material categorizes these pioneers into three distinct evolutionary lineages, each with its own “flavor” of survival.

1. Anthocerotae (The Hornworts): The Enduring Horns

If there were a “weirdest member” award in the plant world, it would go to the Hornworts. Their name comes from their needle-like sporophytes that grow upward like tiny green horns. Unlike other bryophytes, their sporophytes have a Basal Meristem—a zone of active cell division at the bottom that allows the horn to keep growing for weeks or even months. Furthermore, they harbor colonies of Nostoc (cyanobacteria) in mucilage-filled cavities. This is a brilliant survival hack: the bacteria fix nitrogen from the air, providing the hornwort with essential nutrients in exchange for a safe, moist home.

2. Hepaticae (The Liverworts): The Ancient Alchemists

Named during a time when botanists believed in the “Doctrine of Signatures” (the idea that a plant’s shape indicated its medicinal use—liver-shaped for liver ailments), the Liverworts are the most primitive land plants.

- The Thallus: In species like Marchantia, the body is a flat, ribbon-like structure.

- The Gemma Cup: This is one of nature’s most efficient asexual reproduction tools. These tiny cups on the surface of the thallus catch raindrops, which then “splash” out small clones (gemmae) to start new colonies nearby. It’s a low-cost, high-reward strategy for rapid territorial expansion.

3. Musci (The True Mosses): The Architectural Pinnacle

The True Mosses represent the height of bryophyte complexity. They are organized into “stem-and-leaf” bodies (though not true stems or leaves).

- Sphagnum: Known as the “King of Mosses,” Sphagnum is a biological engineer. Its leaves contain specialized Hyaline Cells—large, dead, empty cells with reinforced walls that can hold up to 20 times the plant’s weight in water. This water-storage capacity allows Sphagnum to create acidic, oxygen-poor bogs that effectively stop the process of decay, turning these landscapes into massive carbon vaults.

III. The Life Cycle: A Masterclass in Alternation of Generations

In the botanical “Game of Thrones,” the Bryophytes chose a path that no other land plant group followed: they made the Gametophyte the dominant player.

1. The Protonema: The Secret Beginning

When a moss spore lands on a moist surface, it doesn’t immediately become a moss. It first sprouts into a Protonema—a web of green, algal-like filaments. This is a developmental “echo” of their aquatic ancestors. Only after the protonema is established do the “leafy” buds emerge to form the moss we recognize.

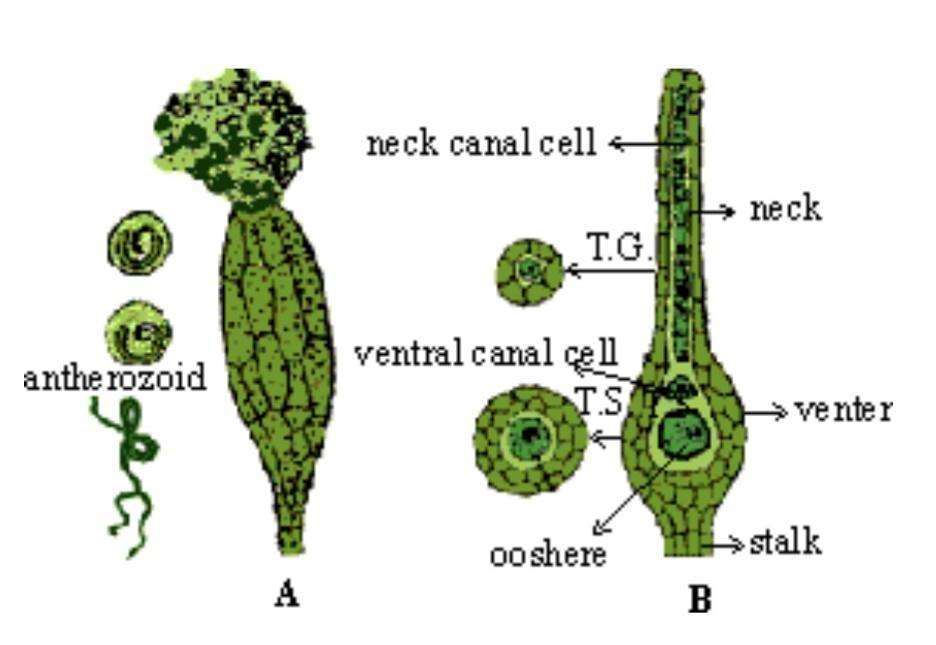

2. The Sexual Theater

Deep within the leafy tips of the gametophyte lie the Antheridia (sperm factories) and Archegonia (egg houses). For a moss to reproduce sexually, it requires a “biological taxi”: water. The sperm are flagellated, meaning they have tails to swim. A single splash of a raindrop can transport sperm from one moss plant to another. This reliance on water is why bryophytes are the “amphibians” of the forest; their sex life is still aquatic, even if their body lives on land.

3. The Dependent Sporophyte: The Hitchhiker

Once fertilization occurs, the zygote grows into the Sporophyte. In a tree, the sporophyte is the tree itself. In a moss, the sporophyte is a tiny parasite. It consists of three parts:

- The Foot: Anchors the sporophyte into the mother gametophyte to steal nutrients.

- The Seta: A long stalk that elevates the spores above the ground to catch the wind.

- The Capsule: A masterpiece of micro-engineering. Inside, it has Peristome Teeth. These teeth are hygroscopic—they move based on humidity. When it’s dry, they open to flick the spores into the wind; when it’s wet, they close to protect the “cargo.”

IV. The Earth’s Unsung Carbon Guardians

We often view moss as a decorative background for garden paths, but their ecological role is titan-sized.

- Soil Creation and Stabilization: Bryophytes are the “scouts” of the plant world. They can grow on bare lava or granite. By secreting mild acids, they slowly dissolve the mineral surface, creating the very first layers of soil. They act as a living net, preventing erosion and allowing higher plants to eventually take root.

- The Peatlands and the Climate Crisis: Peat bogs, largely made of Sphagnum, are the most efficient carbon sinks on the planet. While they cover only 3% of the world’s land area, they sequester more carbon than all the world’s forests combined. When peatlands are drained or burned, they release centuries of stored $CO_2$, making their conservation a frontline issue in climate science.

- Bio-Indicators of Modern Pollution: Because mosses absorb water and minerals directly through their surfaces, they have no way to “filter” pollutants. They are nature’s most honest air quality sensors. Scientists analyze moss tissues to map heavy metal pollution (like lead or cadmium) and nitrogen deposition across entire continents.

Editor’s Epilogue: The Wisdom of Being Small

In our modern world, we are obsessed with “bigness”—tall skyscrapers, massive trees, vast empires. But the Bryophytes teach us a different lesson: the power of the small. They conquered the land by being resilient rather than dominant. They survived five mass extinctions not by fighting the environment, but by adapting to its most brutal whims. As we walk through a damp forest, we are stepping on the very foundations of the terrestrial world.

Join us in Episode 8, as we witness the next great technological leap: the Vascular System. We will explore the Pteridophytes (Ferns)—the first plants that figured out how to build biological “elevators” and finally reached for the canopy.