The Next Level of Organization: How Cellular Differentiation Creates the Specialized Teams That Power Every Aspect of Plant Survival and Growth.

Introduction: The Green Hierarchy

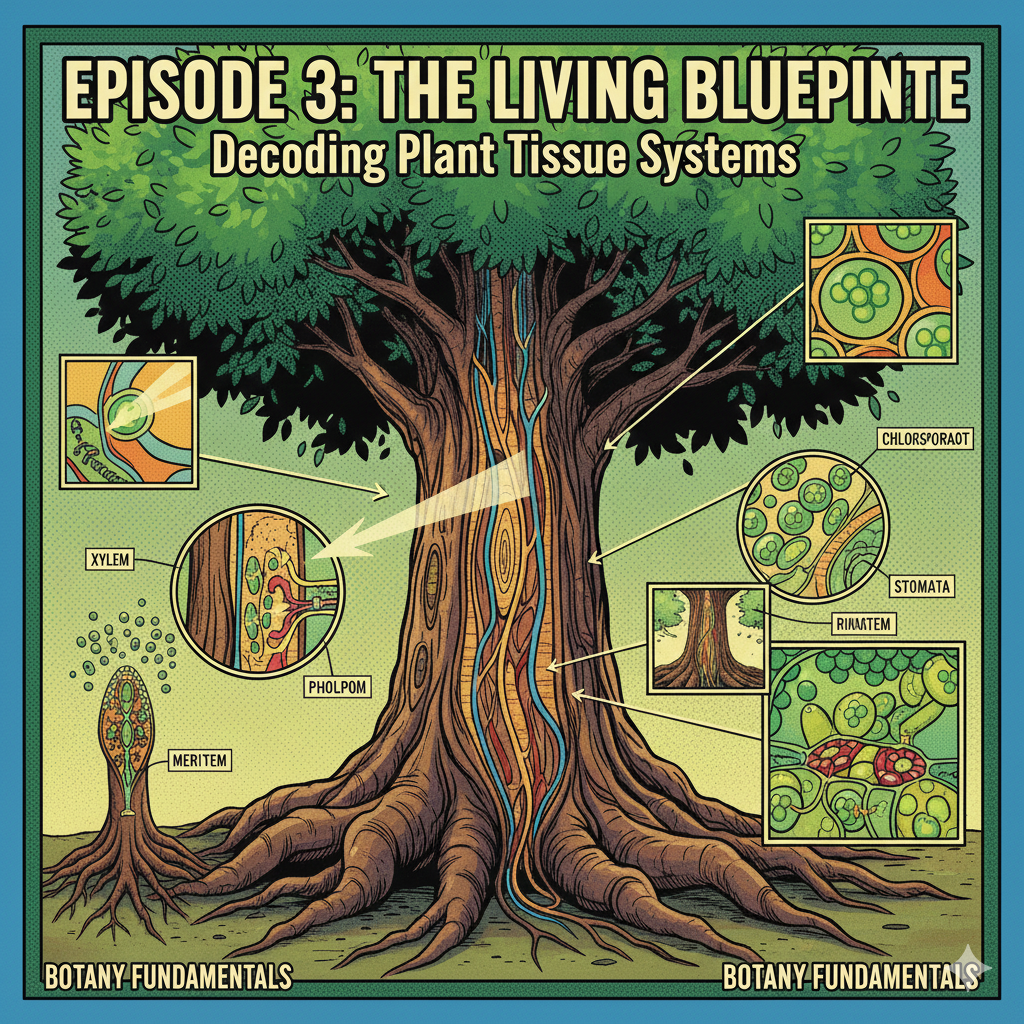

In Episode 2, we mastered the microscopic marvel: the plant cell. We saw how its unique organelles—the rigid Cell Wall, the energetic Chloroplasts, and the pressure-regulating Central Vacuole—make green life possible. Now, we zoom out to the concept that transforms a single cell into a complex organism: The Tissue.

A Plant Tissue is defined as a group of cells, uniform or diverse in type, originating from a common source, that are structurally organized and functionally coordinated to perform a specific task. This specialization, known as cellular differentiation, is the evolutionary leap that allowed plants to achieve their immense size, complexity, and remarkable environmental resilience. Tissues are the specialized materials and systems—the compound and simple structures—that constitute the entire body of the plant.

I. The Dynamic Duo: Meristematic vs. Permanent Tissues

Plant tissues are functionally classified into two major, interconnected categories based on their capacity for division:

A. Meristematic Tissues (Meristems): The Growth Engines

These tissues, often called the “stem cells” of the plant, are composed of continuously dividing, undifferentiated cells. They possess dense cytoplasm and large nuclei, fueling all growth mechanisms.

- Apical Meristems: Located at the tips of roots and shoots, responsible for primary growth (increasing length). They drive the plant’s vertical search for light and water.

- Lateral Meristems: Responsible for secondary growth (increasing girth/diameter). The most notable is the Vascular Cambium, which generates the wood and bark necessary for structural strength and long-term survival.

- Intercalary Meristems: Found between mature tissues, common in grasses, allowing rapid regrowth after grazing or cutting.

B. Permanent Tissues (Mature Tissues): The Specialists

These cells have stopped dividing and have fully undergone differentiation to perform specific, often vital, structural, protective, or metabolic roles. They form the bulk of the mature plant body.

II. The Three Interconnected Tissue Systems

Permanent tissues are organized into three integrated systems, each playing a critical role in the plant’s survival strategy:

1. The Dermal Tissue System: The Security Force

This system forms the plant’s protective exterior—the first line of defense against pathogens, mechanical damage, and desiccation.

- Epidermis: The outermost layer of young stems and leaves. Epidermal cells often secrete a waxy layer called the cuticle, an indispensable feature for drought resistance and controlling evapotranspiration. Key structures like stomata (气孔) are embedded here for gas exchange.

- Periderm: The tough, corky protective tissue that replaces the epidermis in older, woody stems and roots, forming the plant’s bark.

2. The Ground Tissue System: The Core Functionality

This is the most versatile and voluminous system, occupying the space between the dermal and vascular tissues. It handles storage, photosynthesis, and overall structural integrity.

- Parenchyma Tissue: The most abundant and multi-functional tissue, often involved in metabolism, photosynthesis (in leaves), and long-term storage (e.g., starch in roots and stems).

- Collenchyma Tissue: Provides flexible, plastic support to actively growing parts of the plant (like young stems and petioles). Its cells have unevenly thickened primary walls.

- Sclerenchyma Tissue: Provides rigid, non-flexible structural support. These cells often possess thick, lignified secondary walls and are frequently dead at maturity. They include Fibers (long, slender cells, commercial source for textiles) and Sclereids (isodiametric stone cells, responsible for the gritty texture of fruit like pears).

III. The Vascular Tissue System: The Supply Chain

This is the plant’s highly complex and essential “plumbing system,” responsible for transporting materials and linking all parts of the organism.

- Xylem : The primary channel for the unidirectional transport of water and dissolved minerals from the roots upward. Its main conducting elements (tracheids and vessel elements) are non-living (dead and hollow) at maturity, forming an open, low-resistance pipeline that is the fundamental component of wood.

- Phloem: Responsible for the bidirectional transport of organic nutrients (sugars, hormones) produced during photosynthesis. Phloem conducting cells (sieve elements) are alive at maturity but lack nuclei, relying entirely on adjacent, nucleated companion cells for metabolic control and function—a brilliant example of cellular cooperation.

IV. Specialized Secretion Structures: The Chemical Defense

Beyond the three main systems, plants possess highly specialized secretory structures that function as chemical factories, often driving plant defense mechanisms or interaction with the environment.

These include external secretory structures that release compounds to the outside, such as glandular hairs , nectar glands (Nectaries ) used to attract pollinators, and hydathodes used for water removal. Internal secretory structures store compounds within the plant body, such as resin ducts. These chemical systems are increasingly studied for applications in medicine and sustainable bio-materials.

Your Next Step in the Green World

The plant body is an evolutionary masterpiece built upon the precise specialization and tireless teamwork of its various tissues. From the structural integrity provided by Sclerenchyma to the efficient supply chain of the Xylem, every tissue plays a non-negotiable role. By understanding these systems, we gain insight into the fundamental mechanisms of all agriculture and ecology.